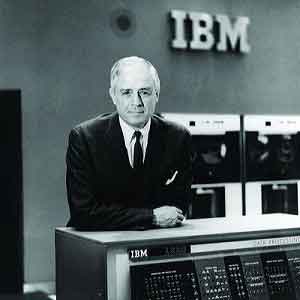

Thomas Watson Jr.

Introduction

Thomas John Watson, Jr. (January 14, 1914 – December 31, 1993) was an American businessman, political figure, and philanthropist. He was the 2nd president of IBM (1952–1971), the 11th national president of the Boy Scouts of America (1964–1968), and the 16th United States Ambassador to the Soviet Union (1979–1981). He received many honors during his lifetime, including being awarded the Presidential Medal of Freedom by Lyndon B. Johnson in 1964. Watson was called "the greatest capitalist in history" and one of "100 most influential people of the 20th century"

Early Life

Watson Jr. attended the Hun School of Princeton in Princeton, New Jersey. He claimed in his autobiography that as a child he had a "strange defect in his vision" that made written words appear to fall off the page when he tried to read them. As a result Watson struggled in school, and he acknowledged that Brown University reluctantly admitted him as a favor to his father. He obtained a business degree in 1937. He married Olive Cawley (1918–2004) in 1941. They had six children.

After graduating Watson became a salesman for IBM, but had little interest in the job. The turning point was his service as a pilot in the Army Air Force during World War II. Tom Jr. became a Lieutenant Colonel flying military commanders. Tom Jr. later admitted to journalists that the one career he would have liked to follow was an airline pilot.

Watson returned to IBM at the beginning of 1946. He was promoted to be a Vice President just six months later and was promoted to the board just four months after that. He became Executive Vice-President in 1949.

Life at IBM

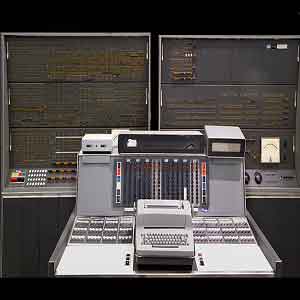

Tom Watson, Jr. became president of IBM in 1952. Up to this time IBM was dedicated to electromechanical punched card systems for its commercial products. Watson, Sr. had repeatedly rejected electronic computers as overpriced and unreliable, except for one-of-a-kind projects such as the IBM SSEC. Tom Jr. took the company in a new direction, hiring electrical engineers by the hundreds and putting them to work designing mainframe computers. Many of IBM's technical experts also did not think computer products were practical, since there were only about a dozen computers in the entire world at the time.

Until the late 1950s the custom-built US Air Force SAGE computerized tracking system accounted for more than half of IBM's computer sales. The company made little profit on these sales but, as Tom Jr. said "It enabled us to build highly automated factories ahead of anybody else, and to train thousands of new workers in electronics."

Tom Jr.'s decision was justified; in the longer term it redirected IBM to its later position dominating the computer market. Even in the short term it paid off; for revenues more than tripled in six years, from $214.9 million in 1950 to $734.3 million in 1956. This dramatic rate of growth almost matched the wartime years; a better than 30% compound growth rate that Tom Jr. maintained for much of the twenty years of his leadership of IBM. It was a record even better than that of his father.

Despite the presence of his son, Thomas Sr. kept a firm grip on the reins until 1955. Tom Jr. described the position of his father as "He wanted to make me head of IBM, but he didn't like sharing the limelight."

Emphasis on research

Prior to his time IBM had primarily emphasized the sales organization, with a reasonable range of products. Tom Jr., however, promoted the research and development structure that is essential to modern high technology industry. It was under his supervision that the laboratories were built up, to a point where, in the late 1980s, they contained Nobel Prize winners; and to the point where the research and development function could stand on an equal footing with marketing, true to his original objective.

When Tom Jr. started this process in 1949, IBM was reportedly two years behind its main competitor, UNIVAC. In the 1980s, it was arguably up to a decade ahead of anyone else; though its problems since seem to have destroyed much of its strength in this area. In the labs though, they were able to plan speculatively for the future decades in advance, independent and untroubled by commercial demands. It was an ideal environment for an industrial researcher, and highly productive for IBM.

The first result of this was the IBM 7030 Stretch program to develop a transistorized "supercomputer" a hundred times more powerful than the vacuum tube 704. It failed to meet its price and performance goals, at a reported cost of $20 million. One of IBM's strengths was that, until the 1980s, it really did learn from experience. IBM made very good use of these particularly hard earned lessons.

The three computer families that eventually emerged from 1958 onwards comprised the IBM 7070 and IBM 7090 for large government business, the IBM 1620 for the scientific community and the IBM 1401 for commercial use. Despite the fact that many observers believed that Tom Jr was frittering away the resources his father had built up, these new ranges were remarkably successful, doubling IBM's sales once more over the six years from 1958 ($1.17 billion) to 1964 ($2.31 billion), maintaining IBM's dramatic growth rate virtually undiminished at approaching 30% compound. The effect was that IBM had become independent of outside funding.

In the early 1960s he oversaw the IBM System/360 project, which produced an entire line of computers that ran the same software and used the same peripherals. Since the 360 line was incompatible with IBM's previous products, it represented an enormous risk for the company. Despite delays in shipment, the products were well-received following their launch in 1964 and what Fortune magazine called "IBM's $5 Billion Gamble," in the end, paid off.

Fragmentized Organization

In 1956, in a move that became a bi-annual event, Tom Jr. reorganized IBM on divisional lines, to give a decentralized organization, with five major divisions in the US. The new structure comprised:

Data Processing Division — selling to (and servicing) commercial customers

Federal Systems Division — selling to (and servicing) the US government

Systems Manufacturing Division

Components Manufacturing Division

Research Division

He introduced the terminology "line and staff". In his words: "By the mid-'50s just about every big corporation had adopted the so-called staff-and-line structure. It was modeled on military organizations going back to the Prussian army in Napoleonic times." His organization "... provided IBM executives with the clearest possible goals. Each operating man was judged strictly on his unit's results, and each staff man on his effort toward making IBM the world leader in his specialty."

The final element of formal organizational change was the isolation of headquarters staff in Armonk, New York. This was said by him to be in order to be near his family. He lived in Connecticut, where taxes were lower; but kept his staff across the border in New York State so, it has been suggested, that IBM would not be seen as similarly evading taxes. Cynics said it was his fear of nuclear warfare (he owned a fallout shelter).His first book in 1963 discussed his management philosophy.