Henry Ford

The man who gave us Ford

Henry Ford (July 30, 1863 – April 7, 1947) was an American industrialist, the founder of the Ford Motor Company, and sponsor of the development of the assembly line technique of mass production. His introduction of the Model T automobile revolutionized transportation and American industry. As owner of the Ford Motor Company, he became one of the richest and best-known people in the world. He is credited with "Fordism": mass production of inexpensive goods coupled with high wages for workers. Ford had a global vision, with consumerism as the key to peace. His intense commitment to systematically lowering costs resulted in many technical and business innovations, including a franchise system that put dealerships throughout most of North America and in major cities on six continents. Ford left most of his vast wealth to the Ford Foundation but arranged for his family to control the company permanently.

Early Life

Ford was born July 30, 1863, on a farm in Greenfield Township (near Detroit, Michigan).His father gave him a pocket watch in his early teens. At 15, Ford dismantled and reassembled the timepieces of friends and neighbors dozens of times, gaining the reputation of a watch repairman. At twenty, Ford walked four miles to their Episcopal church every Sunday. Ford was devastated when his mother died in 1876. His father expected him to eventually take over the family farm, but he despised farm work. He later wrote, "I never had any particular love for the farm—it was the mother on the farm I loved."

In 1879, he left home to work as an apprentice machinist in the city of Detroit, first with James F. Flower & Bros., and later with the Detroit Dry Dock Co. In 1882, he returned to Dearborn to work on the family farm, where he became adept at operating the Westinghouse portable steam engine. He was later hired by Westinghouse company to service their steam engines. During this period Ford also studied bookkeeping at Goldsmith, Bryant & Stratton Business College in Detroit.

Career

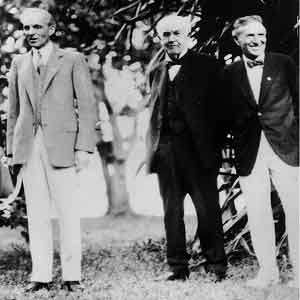

Henry Ford, Thomas Alva Edison, and Harvey Samuel Firestone- the fathers of modernity, at Edison's 82nd birthday. Ft. Myers, Florida, February 11, 1929.

Henry Ford, Thomas Alva Edison, and Harvey Samuel Firestone- the fathers of modernity, at Edison's 82nd birthday. Ft. Myers, Florida, February 11, 1929.

In 1891, Ford became an engineer with the Edison Illuminating Company. After his promotion to Chief Engineer in 1893, he had enough time and money to devote attention to his personal experiments on gasoline engines. These experiments culminated in 1896 with the completion of a self-propelled vehicle which he named the Ford Quadricycle. He test-drove it on June 4. After various test-drives, Ford brainstormed ways to improve the Quadricycle.

Also in 1896, Ford attended a meeting of Edison executives, where he was introduced to Thomas Edison. Edison approved of Ford's automobile experimentation. Encouraged by Edison, Ford designed and built a second vehicle, completing it in 1898. Backed by the capital of Detroit lumber baron William H. Murphy, Ford resigned from the Edison Company and founded the Detroit Automobile Company on August 5, 1899. However, the automobiles produced were of a lower quality and higher price than Ford wanted. Ultimately, the company was not successful and was dissolved in January 1901.

With the help of C. Harold Wills, Ford designed, built, and successfully raced a 26-horsepower automobile in October 1901. With this success, Murphy and other stockholders in the Detroit Automobile Company formed the Henry Ford Company on November 30, 1901, with Ford as chief engineer. In 1902, Murphy brought in Henry M. Leland as a consultant; Ford, in response, left the company bearing his name. With Ford gone, Murphy renamed the company the Cadillac Automobile Company.

Teaming up with former racing cyclist Tom Cooper, Ford also produced the 80+ horsepower racer "999" which Barney Oldfield was to drive to victory in a race in October 1902. Ford received the backing of an old acquaintance, Alexander Y. Malcomson, a Detroit-area coal dealer. They formed a partnership, "Ford & Malcomson, Ltd." to manufacture automobiles. Ford went to work designing an inexpensive automobile, and the duo leased a factory and contracted with a machine shop owned by John and Horace E. Dodge to supply over $160,000 in parts. Sales were slow, and a crisis arose when the Dodge brothers demanded payment for their first shipment.

The Birth of Ford Motor Company

In response, Malcomson brought in another group of investors and convinced the Dodge Brothers to accept a portion of the new company. Ford & Malcomson was reincorporated as the Ford Motor Company on June 16, 1903, with $28,000 capital. The original investors included Ford and Malcomson, the Dodge brothers, Malcomson's uncle John S. Gray, Malcolmson's secretary James Couzens, and two of Malcomson's lawyers, John W. Anderson and Horace Rackham. Ford then demonstrated a newly-designed car on the ice of Lake St. Clair, driving 1 mile (1.6 km) in 39.4 seconds and setting a new land speed record at 91.3 miles per hour (147.0 km/h). Convinced by this success, the race driver Barney Oldfield, who named this new Ford model "999" in honor of the fastest locomotive of the day, took the car around the country, making the Ford brand known throughout the United States.

Model T

The Model T was introduced on October 1, 1908. It had the steering wheel on the left, which every other company soon copied. The entire engine and transmission were enclosed; the four cylinders were cast in a solid block; the suspension used two semi-elliptic springs. The car was very simple to drive, and easy and cheap to repair. It was so cheap at $825 in 1908 ($21,340 today) (the price fell every year) that by the 1920s, a majority of American drivers had learned to drive on the Model T.

Ford created a massive publicity machine in Detroit to ensure every newspaper carried stories and ads about the new product. Ford's network of local dealers made the car ubiquitous in virtually every city in North America. As independent dealers, the franchises grew rich and publicized not just the Ford but the very concept of automobiling; local motor clubs sprang up to help new drivers and to encourage exploring the countryside. Ford was always eager to sell to farmers, who looked on the vehicle as a commercial device to help their business. Sales skyrocketed—several years posted 100% gains on the previous year. Always on the hunt for more efficiency and lower costs, in 1913 Ford introduced the moving assembly belts into his plants, which enabled an enormous increase in production. Although Ford is often credited with the idea, contemporary sources indicate that the concept and its development came from employees Clarence Avery, Peter E. Martin, Charles E. Sorensen, and C. Harold Wills.

By 1918, half of all cars in America were Model T's. The design was fervently promoted and defended by Ford, and production continued as late as 1927; the final total production was 15,007,034. This record stood for the next 45 years. This record was achieved in just 19 years from the introduction of the first Model T (1908).

Henry started another company, Henry Ford and Son, and made a show of taking himself and his best employees to the new company; the goal was to scare the remaining holdout stockholders of the Ford Motor Company to sell their stakes to him before they lost most of their value. (He was determined to have full control over strategic decisions.) The ruse worked, and Henry and Edsel purchased all remaining stock from the other investors, thus giving the family sole ownership of the company.

Model A

By 1926, flagging sales of the Model T finally convinced Henry to make a new model. He pursued the project with a great deal of technical expertise in design of the engine, chassis, and other mechanical necessities, while leaving the body design to his son. Edsel also managed to prevail over his father's initial objections in the inclusion of a sliding-shift transmission.

The result was the successful Ford Model A, introduced in December 1927 and produced through 1931, with a total output of more than 4 million. Subsequently, the Ford company adopted an annual model change system similar to that recently pioneered by its competitor General Motors (and still in use by automakers today). Not until the 1930s did Ford overcome his objection to finance companies, and the Ford-owned Universal Credit Corporation became a major car-financing operation.

Ford did not believe in accountants; he amassed one of the world's largest fortunes without ever having his company audited under his administration.

The revolutionary five-dollar workday

Ford was a pioneer of "welfare capitalism", designed to improve the lot of his workers and especially to reduce the heavy turnover that had many departments hiring 300 men per year to fill 100 slots. Efficiency meant hiring and keeping the best workers.

Ford astonished the world in 1914 by offering a $5 per day wage ($120 today), which more than doubled the rate of most of his workers. A Cleveland, Ohio newspaper editorialized that the announcement "shot like a blinding rocket through the dark clouds of the present industrial depression." The move proved extremely profitable; instead of constant turnover of employees, the best mechanics in Detroit flocked to Ford, bringing their human capital and expertise, raising productivity, and lowering training costs.

Ford announced his $5-per-day program on January 5, 1914, raising the minimum daily pay from $2.34 to $5 for qualifying workers. It also set a new, reduced workweek, although the details vary in different accounts. Ford and Crowther in 1922 described it as six 8-hour days, giving a 48-hour week, while in 1926 they described it as five 8-hour days, giving a 40-hour week. (Apparently the program started with Saturdays as workdays and sometime later it was changed to a day off.)

Detroit was already a high-wage city, but competitors were forced to raise wages or lose their best workers. Ford's policy proved, however, that paying people more would enable Ford workers to afford the cars they were producing and be good for the economy. Ford explained the policy as profit-sharing rather than wages. It may have been Couzens who convinced Ford to adopt the $5 day.

International Business

Ford's philosophy was one of economic independence for the United States. His River Rouge Plant became the world's largest industrial complex, pursuing vertical integration to such an extent that it could produce its own steel. Ford's goal was to produce a vehicle from scratch without reliance on foreign trade. He believed in the global expansion of his company. He believed that international trade and cooperation led to international peace, and he used the assembly line process and production of the Model T to demonstrate it.

Edsel Ford, Charles Lindbergh, and Henry Ford pose in the Ford hangar during Lindbergh's August 1927 visit. He opened Ford assembly plants in Britain and Canada in 1911, and soon became the biggest automotive producer in those countries. In 1912, Ford cooperated with Giovanni Agnelli of Fiat to launch the first Italian automotive assembly plants. The first plants in Germany were built in the 1920s with the encouragement of Herbert Hoover and the Commerce Department, which agreed with Ford's theory that international trade was essential to world peace. In the 1920s, Ford also opened plants in Australia, India, and France, and by 1929, he had successful dealerships on six continents. Ford experimented with a commercial rubber plantation in the Amazon jungle called Fordlândia; it was one of his few failures. In 1929, Ford accepted Joseph Stalin's invitation to build a model plant (NNAZ, today GAZ) at Gorky, a city now known under its historical name Nizhny Novgorod. He sent American engineers and technicians to the Soviet Union to help set it up, including future labor leader Walter Reuther.

By 1932, Ford was manufacturing one third of all the world’s automobiles. Ford's image transfixed Europeans, especially the Germans, arousing the "fear of some, the infatuation of others, and the fascination among all". Germans who discussed "Fordism" often believed that it represented something quintessentially American. They saw the size, tempo, standardization, and philosophy of production demonstrated at the Ford Works as a national service—an "American thing" that represented the culture of United States. Both supporters and critics insisted that Fordism epitomized American capitalist development, and that the auto industry was the key to understanding economic and social relations in the United States. As one German explained, "Automobiles have so completely changed the American's mode of life that today one can hardly imagine being without a car. It is difficult to remember what life was like before Mr. Ford began preaching his doctrine of salvation". For many Germans, Ford embodied the essence of successful Americanism.